Special thanks to Phelps County Focus for featuring this article on November 16, 2023

By Hannah Martinez, Staff Writer at Phelps County Focus

hannah@phelpscountyfocus.com

Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity states that everything is relative—time and even distance depend on the perspective of the observer.

Artists create lifelike perspective, which is the 3-D portrayal of depth and distance using clever mathematics or strategically arranged colors and tones.

A little more than 40 years ago, Dr. Terry Brewer and his wife, Paula, were walking atop a range of high bluffs bordering a river in Minnesota, when a red-tailed hawk soared by them, level with their eyes. For Brewer, who had recently quit his job, intent on starting a new company, the encounter gave him a bird’s eye view of the type of business he wanted to build.

“I saw an abstract story, an abstract representation of the world and also of business and how those all merged into a single view,” said Brewer.

His company, Brewer Science, bears the emblem of the hawk, a logo which Paula designed. The brand is recognized globally for its high-quality products and environmental sustainability and has also received national awards as a top-ranked workplace.

At Missouri S&T’s annual Stoffer Lecture, Chancellor Mo Dehghani introduced Brewer as a key player in the semiconductor industry, before his address, “The Business of Chemistry.”

“Brewer Science is known across the country,” said Dehghani. “When I’m in Silicon Valley, everybody knows Brewer Science.”

But how did a company which produces chemicals for the competitive tech world of semiconductors get started in the foothills of the Ozarks?

“It would really take me a thousand years to try to go through the whole story,” said Brewer. “It’s a little bit like Shakespeare’s plays, there’s layers of meaning.”

Brewer’s education began in a one-room country school in Michigan. As a student he excelled in liberal arts courses like social studies, history and English. However, he was interested in science because he believed that was the best way to learn how the world worked.

He started college as a chemistry major at the University of Michigan, ready to work. Years later, when visiting a high school physics teacher after earning a college degree, his teacher would introduce him, saying, “’This is Terry Brewer and he just got his degree in chemistry, and if Terry can do it, anybody can do it.’”

The first two years of undergraduate work were grueling; Brewer said that he struggled to understand his science courses. He explained that it was hard, because the sole focus of coursework was to digest as much information as possible without taking the time to apply it.

“In the first two years in almost every university program all they want to do is give you information,” said Brewer. “I want to have understanding, not just knowledge.”

Before completing his bachelor’s degree, Brewer transferred to the University of North Texas, a small school known for its music program with an unremarkable science reputation. But the new environment afforded him hands-on opportunities and Brewer was conducting graduate-level research as an undergraduate student.

“People recognized my questioning and pursuit of understanding, and so they supported it,” said Brewer. “It was small enough, you could get that sort of customized, non-programmed kind of training. So, that’s when it started to be a joy.”

After continuing his pedigree to include a Ph.D. in chemistry from North Texas, Brewer went to the University of Texas and completed a post-doctorate, eventually landing a job at Texas Instruments, a company in the semiconductor industry which he “knew nothing about.”

“It was one of those serendipities that turned out really well. But it’s like going to school, going from Michigan State, going to North Texas,” said Brewer. “It was kind of a string from a farm schoolhouse all the way through to a semiconductor company in the end.”

Although he enjoyed the science, Brewer learned that the large corporate environment wasn’t a good fit, so after six years he transferred to a position at another semiconductor company, Honeywell, in Minneapolis.

Despite noticing a less politically charged atmosphere, Brewer still felt limited by the company’s structure and bureaucracy, which made him feel stifled. While working there he discovered some revolutionary technology to potentially disrupt and improve the industry, but the company brushed it off as irrelevant.

“I wasn’t interested in security or titles, I was more interested in what I could do, what we could change, what we could make better,” said Brewer. “So, I quit my job at Honeywell and didn’t know what I was going to do.”

Already in Minnesota, Brewer looked into starting a business in Duluth. In Minneapolis a network of free lawyers, advisory boards, accountants and mentors was available for fledgling entrepreneurs like Brewer to get started. Brewer recruited a handful of private investors interested in his business plan, but there was a catch: they would only leave him 25% of the business.

“Because I was a scientist by trade, they made the assumption that I could not run a business. So, I would be in some job that would be directing research but not running the business.” said Brewer. “I didn’t want to just start a business for the science, I wanted to start a business to create an environment where maybe people would rather come to work.”

Since starting a business in Minnesota wouldn’t be possible without surrendering 75% of the business, Brewer was pounding the pavement looking for private companies interested in his technology without success. However, through networking, he became aware of a small electronic chemical company called Mead Chemical in Rolla.

Since Brewer had an impressive resume working with electronic chemicals, he was offered a job, but he had other ideas.

“I said, ‘I’ll come if you’ll help me start my own company,’ so that’s what we did. I came and helped them with their chemistry and they helped me get started here.”

Brewer was able to use half of a warehouse and repurpose some of the equipment from his associates’ chemical-making to create his own chemical products. During the first year, he lived and sold to clients from an RV, while his family was still living in their home in Minnesota.

Visiting clients was more than a chance to sell, it was also an opportunity for Brewer to get more parts for his product development.

“A lot of semiconductor companies have warehouses full of old, used equipment, and I knew about that because I’d worked in a couple of them,” said Brewer. “I’d ask them to go to their warehouse and look at their equipment and I would find pieces of equipment that I wanted to bring home and fix up and put them on a U-Haul behind my RV.”

Even though money was tight with the startup being barely over a year, Brewer’s family bought a modest home in Rolla, and he continued burning the midnight oil to make something the world had never seen.

The first products Brewer developed and sold were test sample kits.

“The chemical was an antireflective coating which didn’t exist in the industry and the industry was having trouble doing their manufacturing photochemistry on the circuits, and my materials were designed to help improve that capability,” said Brewer. “They had never heard of it, they were reluctant to try it.”

After two years, the test sample kits had established some goodwill and larger quantities were purchased by government-funded electronic companies.

Ten years in was when things really started to take off. Cell phone companies like Motorola took notice and started using Brewer’s material for cellphone components. “That’s when we actually started to behave like a real commercial supplier,” said Brewer.

The business expanded to European markets, and then Japan. “After the commercial demand started, the products evolved further forward. The industry is really specialized and customized, so it was very difficult to develop one product that worked for everybody—everyone seemed to have a variation,” said Brewer.

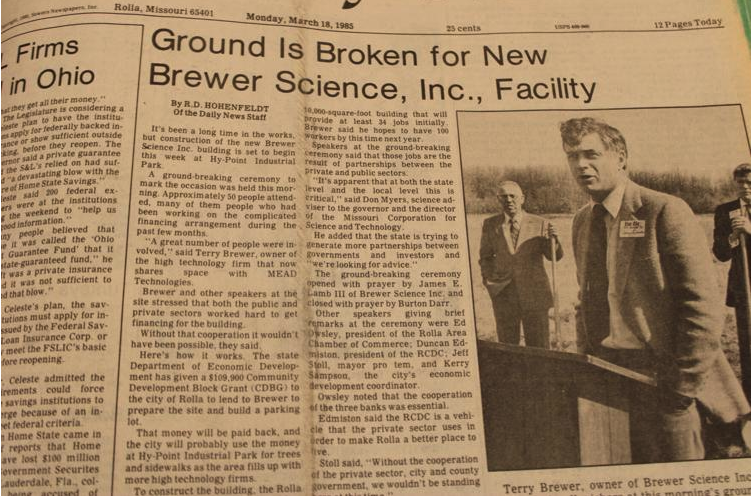

The manufacturing for varied customer needs necessitated more space. So, in the 80’s the original 10,000square-foot facility at the industrial park was built. “We had this building and we did everything here. We did R&D and we had manufacturing,” said Brewer.

In 1983 the original 10,000 square-foot Brewer Science facility was built at the industrial park.

Photo by The Rolla Daily News

Brewer’s anti-reflective coatings have been instrumental in making better, more compact components for cellphones, computers, etc. The flagship Rolla facility has grown almost 5 times its original size with additional presences in Vichy and Springfield, Missouri, United Kingdom, South Korea, France, Japan, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The company employs about 500 people who have the impossible task of inventing products which no one has ever made before. The company currently holds over 175 U.S. patents, proving that it can be done over and over again. “It’s a complex matrix of possibilities that we have to put together,” said Brewer. “It’s mind blowing the science that goes on here.”

Not only does the company deal with the challenge of invention, according to Brewer his is the only company in the United States manufacturing semiconductor chemicals to survive past 2008. Currently the industry is in an economic “trough” of decreased demand, but the company has weathered eight other economic downturns.

Brewer said many are mystified by the company’s success in a small town in Missouri. The semiconductor industry is one of the most technical, specialized and competitive industries in the world. With semiconductor hubs primarily along the United Stated coasts or near them, it defies understanding that Brewer has stayed relevant for so long.

“I don’t have to be someplace or be somebody to determine who I am or who this company is. That’s a very fundamental statement backed up now with over 40 years of evidence that it’s true, and people don’t ever really get it,” said Brewer. “The funny part about it is that it’s not about an answer, it’s about understanding—moving into the open space of possibilities and living in that world of possibility.”

During the Stoffer lecture, Brewer challenged students not to expect “answers.” He shared that one of the biggest challenges in running a business is change and that the key to staying successful is to change your perspective and to use failures to learn effective processes.

“I try to run the company along the lines of quantum mechanics. As you know from quantum mechanics: context is ever changing and the measurements in quantum mechanics are dependent on the observer,” said Brewer. “I’m happy living in our space where there’s no dimensions and no edges.”

For more information, visit brewerscience.com.